commitments

how do you frame freedom for yourself?

One of my favorite questions to ask people when I’m trying to understand how their mind works is “how do you frame freedom for yourself?” It’s a loaded question that gets taken in a million different directions and that’s why I like it. I’ve gotten everything from blank stares to “backpacking” to “when I make 10M dollars.”

For me, freedom always used to mean complete and utter independence. I thought if I got out of my tiny town, graduated from the right school, and got the perfect job, I’d finally feel free. In my mind’s eye I always imagined freedom would feel like flying and fully believed that once I spiritually took to the air, I’d finally feel at peace.

More recently though, I reached that supposedly peaceful place. I’ve been a complete and total free bird for the last few months — no one I need or owe anything to in sight. And guess what? All I seem to be capable of doing with these wings is spiral in tight sequential circles. I’ve felt lost and confused, unable to wayfind anything that might provide me direction or a sense of purpose. I thought that with freedom’s high-level perspective I’d subsequently be able to spot where meaning was hiding somewhere within me, but so far I’m just not seeing it.

And the truth is, maybe that’s never how it’s worked for anyone anyway. As Aristotle articulates, freedom used to mean the “cultivated ability to exercise self-governance, to limit ourselves in accordance with our nature and the natural world.” He conceived of freedom as independence from our base desires — which implies that in order to attain it, we can’t necessarily ‘live as we like.’ This is crazy considering the fact that our current cultural conception of freedom (that we adopted from Rousseauian liberalism) is essentially the opposite: ‘doing away with obligation to anyone or anything other than ourselves.’

Rousseau’s freedom is exactly what I’ve been experiencing these past couple of months and what prompted me to wonder why we’re so wimpy. What I was really asking was why am I so wimpy. Or more specifically: Why do people (me) find it so hard to commit? Why do we (me) even idealize this conception of freedom in the first place?

Now, I’m not an isolated incident. I’ve watched far too many friends flounder once they attain freedom for me not to mypothesize (Molly hypothesis) that this is an American culture problem writ large. After all, our Declaration of Independence says life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — but it gives basically no instructions beyond that. Any good editor would have told the founding fathers to go back and add more detail, for the love of god.

Now, this not-knowing-what-you-want thing is something I can empathize with deeply. America and I have a lot in common. We both have always positioned ourselves in relation to other existing entities and ideologies (in America’s case, declaring independence from Great Britain and in my own, renouncing regular jobs). This works right up until you get too good at achieving what you thought you wanted and are faced with the deeply unsettling question of “what now?”

America and I are now in the middle of our “what now?” era. We both have achieved the Rousseauian freedom we thought we so desired, yet find ourselves searching for something more. The truth is that freedom is an empty aspiration with no endpoint: there will always be more spiritual shackles to take off until we are attacking our very selves to do so.

And on a national scale, it’s not just that we’re optimizing for freedom because we don’t know what we want — America has also grown to like being stuck in this not knowing, thinking it to be part of our charm as opposed to a temporary awkward teenage phase in our nation’s history. It’s both hubris and habit: we’ll defend freedom till our dying breath because we’re spent three adult lifetimes acquiring options and at this point, it’s all we’ve built a track record of being good at (relatable).

It’s easy to invalidate this problem by saying that we Americans have everything we could ever want and shouldn’t be complaining. While that’s one way of looking at it, such a response also strikes me as cope to avoid facing the unsettling reality that in an age where our nation is the wealthiest it’s ever been1, we seem to be set on a dangerous trajectory toward the utter dissolution of any shared commitment to the things that have historically made life worth living — like family, friends, and broader connection2.

True freedom of the soul cannot exist purely in opposition to something else — it has to be born from finding something we positively want to be. So perhaps a better question to ask ourselves than “how do you frame freedom for yourself?” is “what do you really want?” Personally, I want to be a mom and have a family and a cat. I want to play in the world of ideas, make beautiful things, and tell stories that change peoples’ minds. I want a neighborhood of close friends to host dinners for and sense-make with. I want to feel proud of the slice of earth that I exist in and a sense of responsibility to leave it better than I found it.

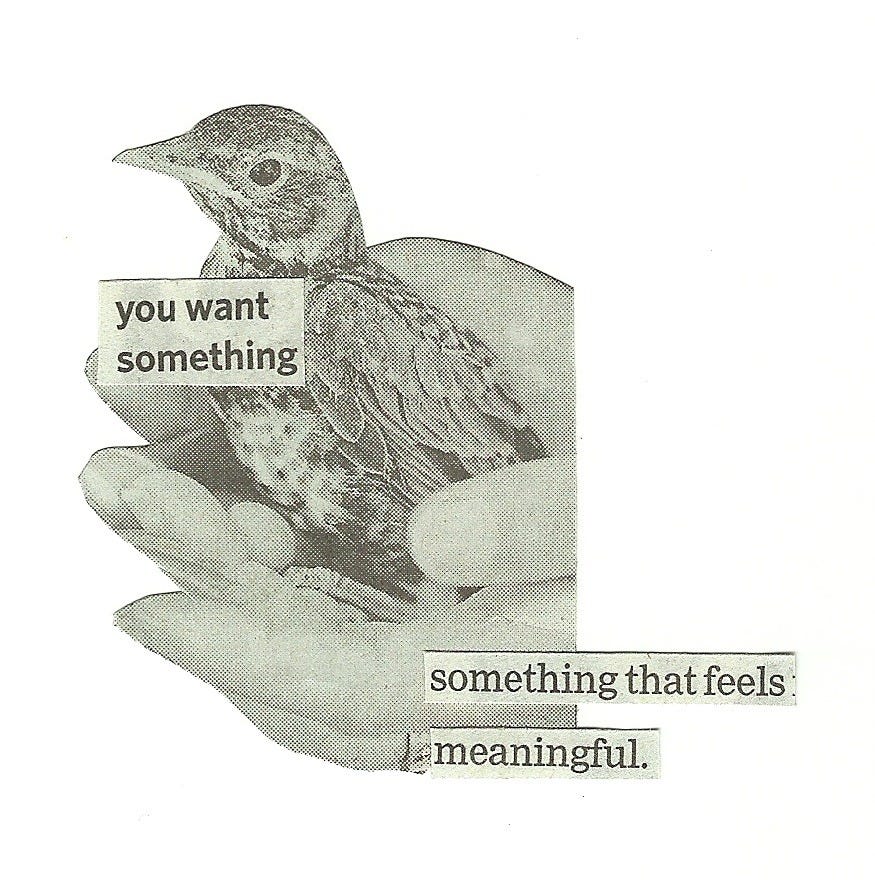

As Aristotle clearly understood eons ago, there’s something undeniably romantic about responsibility — a fact that blindly optimizing for Rousseau’s freedom might make you forget but you’ll still feel if you lack grounding ties. After all, even free birds return to their nests at night. This is why our definition of freedom matters — freedom in a purely rights-based sense alone will never grant a feeling of a life well-lived. When I'm looking back from my deathbed, I doubt I’ll have anything to say for the freedom I felt — instead I’ll be reminiscing on the pride I earned from the commitments I made.

That’s my answer as to why I’ve been so wimpy. I’ve been chasing after a framing of freedom that directly rejected responsibility to the people, places, and projects I now know provide the sense of purpose I was craving all along.

What I’m trying to say is that committing to stuff is cool — and a potent personal-scale antidote to wimpiness. I have high aspirations for human beings and think we can all do and be better — I’m just still trying to figure out how, exactly. I’ll be the metaphorically winged test subject and let you know what I learn.

According to an annual tally by the German insurer Allianz, America is the wealthiest nation on the planet and in all of history.

“ Any good editor would have told the founding fathers to go back and add more detail, for the love of god.” Heehee! 👏

I think you’re right! A few other nuggets that could be worth exploring —

1. The Civil Rights movement has long had a gorgeous, nuanced conception of Freedom that I find deeply appealing on a soul level. You could say all the spirituals are about freedom from literal slavery, but I think there’s more than that. There is a kind of freedom TO — to be the best that we can be as a people, not just racially defined but as a collective who loves each other, under God. There is a sense that it matters HOW we are, not just merely whether we are acting as we desire. At least that’s what I hear and love when I hear “freedom” sung.

2. I highly recommend Maggie Nelson’s book “On Freedom” because it looks at this constellation of ideas so keenly and beautifully. Responsibility, care, constraint… all these concepts feature in the book. It could be useful. She’s also married, a mom, and I don’t know if she has a cat but! You get my gist ;) she seems both extraordinarily radical and smart, but also grounded in a family she decided to make with her one wild and precious life.

Good luck!!!

I've been fascinated by Kierkegaard's definition of “anxiety" as "the dizziness of freedom” -- when one lacks all commitments, and has total freedom, anxiety is what arises. I find that well-placed commitments are also what brings purpose in my life - commitments to partners, friends, cats, companies.

And as we've been chatting about over pancakes, my commitments also go through periods of transformation (🐍🐛🦋) - and this quote has been my guide during those moments: “Don't surrender all your joy for an idea you used to have about yourself that isn't true anymore.” ― Cheryl Strayed, Tiny Beautiful Things

Thanks for writing this ❤️